Atlanta, Hip-Hop and the 1996 Olympics

Atlanta, Hip-Hop and the 1996 Olympics

Published Sat, November 21, 2020 at 8:47 AM EST

"I wasn’t even really paying attention to the Olympics. That was on some white folks shit..."

The 1996 Olympics are like a line in the sand for so much of Atlanta's contemporary history. The Summer Games came to capital of the Peach State touting lofty ambitions for the event's centennial; and the city was eager to welcome the world. At least, that was the narrative pushed by so much mainstream media at the time. But for Goodie Mob member Khujo, whose group was enjoying the success of its debut album Soul Food around the time the Games came to Atlanta, that time will always be more bitter than sweet.

"It was something big that came to the city," Khujo concedes. "It’s big coming through any city. I could see everybody wanting that shit to happen. But there was an undertone of what [else] was going on in the city. I think that’s what OutKast and Goodie Mob and the Dungeon Family was obligated to do: tell the truth about what the fuck is going on. The news is only gonna tell you so much."

What so many outsiders didn't see were the drastic changes that began happening around Atlanta in the run-up to the games. An impoverished inner city was suddenly, irrevocably expendable to a growing metropolis and its ever-heightening aspirations. From 1990 through 1996, there was an Atlanta that certain people certainly wanted to celebrate; and there was another Atlanta that someone clearly wanted to bury. "Atlanta City Guides" printed up for tourists virtually ignored South Atlanta entirely.

In advance of the 2016 Games in Rio de Janeiro, RioOnWatch reported on Atlanta's Olympic-related gentrification:

"The area around the Olympic stadium in Atlanta, host of the 1996 Games, became the Centennial Olympic Park which was sold to residents as an open public space but condemned by urban geographer Charles Rutheiser as “an ephemeral simulation of an open public space.”

New laws would be issued; making it a criminal offense to do things like take things from public trash cans. There were reportedly almost 10,000 arrests of disenfranchised Atlantans in the year and a half prior to the 1996 Summer Games. Homeless panhandlers were issued one-way bus tickets to their hometowns or anywhere that they had relatives, signing off on promissory notes that they wouldn't come back.

And the main drive for such tactics was, per usual, the money the city stood to make from hosting the Games. This was a massive undertaking and a chance for Atlanta to announce it had reached "the big time." According to Atlanta and the Olympics: A One-Year Retrospective, the Atlanta Games drew more than 10,000 athletes from 197 countries. More than two million visitors attended the Games and another 2.5 billion watched them on television.

Over three decades as Executive Director of Atlanta's Task Force for the Homeless, Anita Beaty has been an advocate for the city's most disenfranchised for decades. "Even progressives in Atlanta were, horrifyingly, going along with everything, and saying, 'Y’all over there need to just chill, because it’s just going to last for two weeks, and then we’ll get back to normal,'" Beaty, who retired in 2017, said in 2016. "And we said, 'Normal? We’ll never be back to normal.' And that has been absolutely true."

In the lead-up to the '96 Games, officials also targeted the city's projects for drastic, systemic regulations and policing. The city pioneered the idea of housing projects, and by the early 1990s, the Atlanta Housing Authority owned roughly 14,000 individual units across 43 properties. Techwood Homes, the notorious housing projects that was the nation's first official public housing, sat adjacent to Georgia Tech and near Coca-Cola in what is now considered West Midtown. Techwood was repurposed as Olympic housing and that neighborhood was forever changed.

It was only one example of how the city displaced millions of its residents in public housing. Offering relocation vouchers and demolishing facilities far faster than any other major urban center, Atlanta committed itself to a drastic facelift that echoed long after the Games ended.

“They think because we live in the projects that we are the projects," activist Diane Wright, community advocate for the now-destroyed Hollywood Courts housing, said in the 2008 documentary The Atlanta Way. "We're human beings first and foremost, and we're residents who want to have something,” she explained. “If you're going to tear down a property and displace people, they should have the opportunity to speak out.”

Throughout Goodie Mob's debut album, there are references to changes happening in their city. Mentions of streets being blocked off, Lovejoy jail, Mosely and Maddox pepper classic songs like "Live At the O.M.N.I." and "Goodie Bag."

"Gipp saying 'Somebody turn the lights on on [Georgia highway] 166,'" Khujo mentions. "Next thing you know, they got lights all down 166! So somebody was listening."

Soul Food documents a city in transition and a community under economic attack. There was a palpable anger in Khujo, Gipp, T-Mo and Cee-Lo talking about what was happening throughout Atlanta, while the city put on for the out-of-towners. A part of Goodie Mob (and the Dungeon Family) ethos was authenticity. They spoke for a community that even Hip-Hop had never paid much attention to -- and it was the perfect time to be a voice.

"I think it was a cry out," Khujo says. "Us being so hamstrung -- where the South was pegged as one type of thing. Then all of a sudden, when it’s time to do it, you got all kinds of stuff going on in our city. You’ve got the Olympics and the gentrification of a city -- when gentrification wasn’t even a word at that time."

Much in the same way that a Biggie reference to Rudy Giuliani had non-New Yorkers despising the former Mayor, Goodie Mob explaining how things were in the ATL gave outsiders a deeper, more nuanced take on a place that had been largely absent from contemporary Black popular culture up to that point. Even though southernness inherently informs so much American Blackness.

"The South is a hub," says Khujo. "But you had people who moved away from The South to find work up North. But their family still had ties in the South. It was all related."

Atlanta, Georgia - Photo by Rehder Carsten/picture alliance via Getty Images

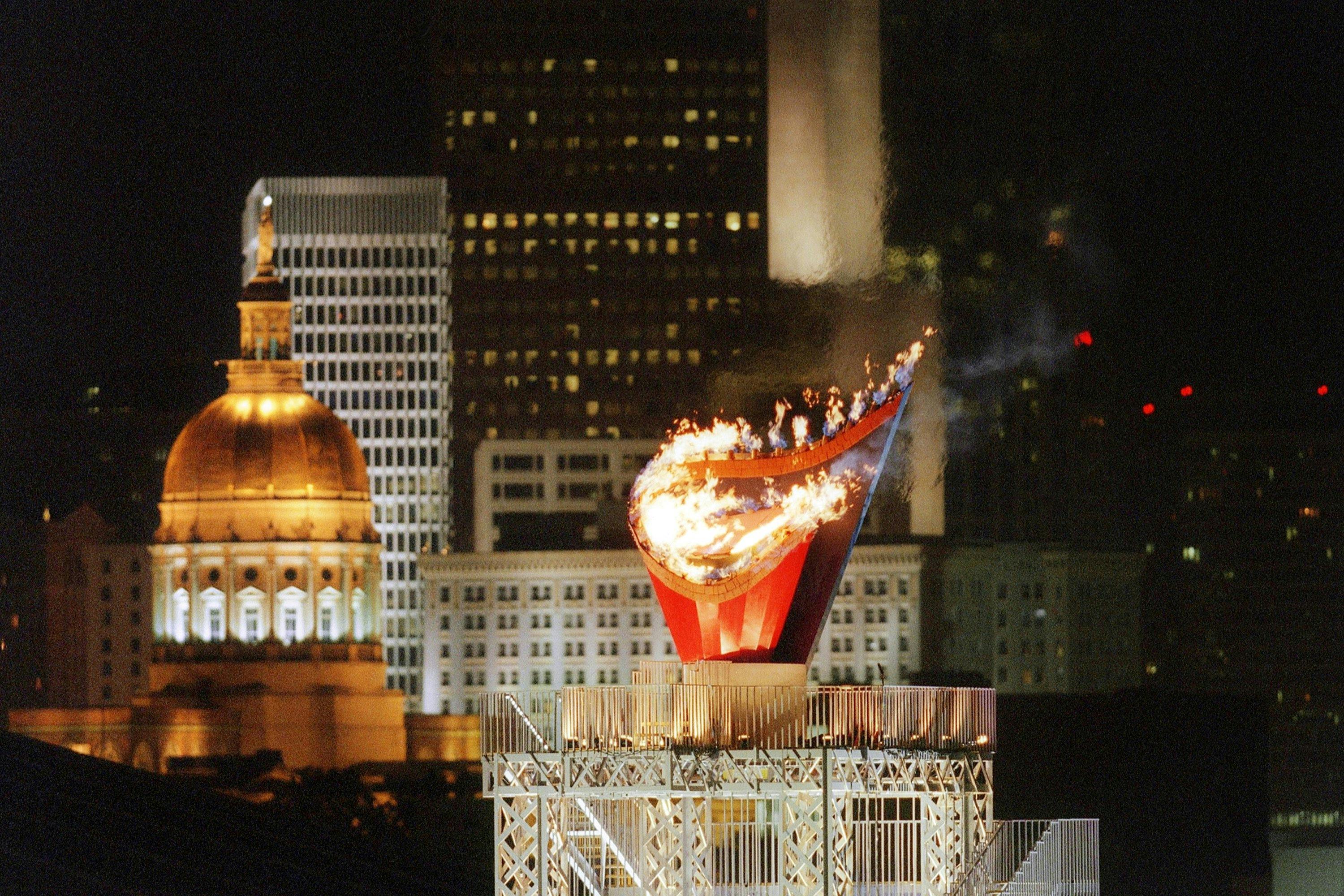

The Olympic flame as seen in front of the skyline of the southern Georgian city of Atlanta early 20 July 1996 at the end of the Centennial Olympic Games opening ceremony. Photo: PEDRO UGARTE/AFP via Getty Images

Mid-way through the 1996 Olympics, of course, Eric Robert Rudolph detonated a bomb at Centennial Olympic Park that killed two people and injured others. That bombing cast a dark cloud over the gaudiness of the Games that year, and it came to crystallize the double-sided legacy of the 1996 Olympics. There was a very big show, but it couldn't smooth over an undercurrent of ugliness. It was a time when the city put on its best face, but not necessarily its most authentic face, to take its place on the world stage. But even while inflatable beer cans and confetti rained down, there was an entire culture thriving in this now-Olympic city that wasn't all that moved by the festivities. And Goodie Mob gave voice to that world.

"Being able to put those landmarks in the music and to be able to recognize and document that shit in the music; it was more than just rap," says Khujo. "It was damn-near a history of Atlanta from the eyes of the youth. We happened to be on LaFace Records [and] able to relay that message globally."